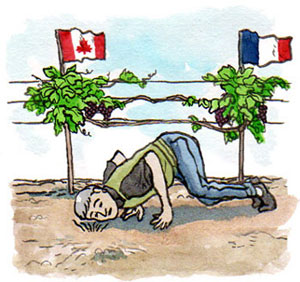

For Le Clos Jordanne’s Burgundian-trained winemaker – Thomas Bachelder – Terroir Winemaking means listening carefully to what the soil is saying in each vineyard parcel.

Expressing Terroir through Pinot Noir: an interview with Thomas Bachelder of Le Clos Jordanne

"I didn’t come home out of dumb sense of national pride. I came because the potential flavours here excited me."

by

Tony Aspler

September 26, 2006

Tony Aspler (TA): What are the varieties that can be successfully grown on the Niagara Escarpment and why?

Thomas Bachelder (TB): This is a very personal subject for me, being an ex-journalist. To start with, I believe that there are interesting cool-climate varieties from Eastern Europe that have barely begun to be tapped. There are surely some great treasures awaiting us there, but as they haven’t yet discovered and marketed them successfully to a broader market themselves, it sure isn’t up to us in Niagara to do it first!

it sure isn’t up to us in Niagara to do it first!

So, working with the grape types we already know, and mindful of Niagara’s need to focus, I would favour only three cool-climate ones that have an affinity for calcaire (limestone). What I mean by that is: varieties that in the presence of limestone show thrilling floral notes, racy acidity and elegant minerality, which create the signature of a ‘sense of place’. To me, that would be: Pinot Noir; Chardonnay; and Riesling. Period. After that, perhaps Gamay (it prefers granitic soils, though) and Cabernet Franc. But Aligoté could be tested; as could Melon de Bourgogne (it is at Malivoire); Auxerrois; Pinot Blanc and Pinot Gris; Grüner Veltliner, and St. Laurent from Austria (Karl Kaiser at Inniskillin did these, but not, I believe, on the Bench). Some of these have winter hardy issues, though.

TA: In your opinion are too many varieties being grown there?

TB: Far, far too many! We need to focus, like other recent emerging regions have: Oregon, Central Otago; Washington. Niagara is both blessed and damned to have Toronto and Buffalo so close. The ready market has kept us from lifting our eyes to the world stage, which means we have remained provincial and unfocussed in our choices, or lack of them!

TA: What is it about the Escarpment that makes it different from vineyards on the plain?

TB: First, it is close enough for lake effect -- it is actually warm up here in summer! And yet, it also has slope, drainage; and that heady mix of glacial till (limestone) and silty sand that seems to imbue these wines with an outrageous perfume and a sense of place to boot! The glaciers brought limestone to the Canadian Shield in a very heterogeneous way. That is to say no two vineyards are alike. We’re finding huge differences in the soils and wines made thereon even within our single-vineyards.

TA: Why did you choose to leave Oregon to make wine in Ontario and what is the major challenge in this region?

TB: I like concentrated wines, but I love racy wines. I’m all about concentrated cool climate. I prefer wines that ally finesse, perfume and power. Power alone rarely impresses my palate. I like wines that you’re still smelling after the meal is over and the glass is empty. Wines that evolve over the course of a meal.

So, as an example, if I’m in a wine store that has every grower and village in Burgundy represented, my hands will unerringly reach out for the terroirs that best capture the duality of raciness, aroma and power. Chambolle, but of course! But also and equally, Vosne-Romanée, Volnay, even the best crus of Pernand (Ile de Vergelesses), all at least at the 1er Cru single-vineyard level.

Pinots from the minerally soils of Chassagne, Santenay and Nuits are in another category for me: perfumed and racy, but with a harder, iron-tasting core. I like those just as well, but in a more intellectual and less hedonistic way. Others, like Pommard, Corton, Savigny and Beaune strike me as being big, solid, lush Pinots that often fail to ‘make me dream.’ There are of course, exceptions.

This is not to say that Oregon doesn’t also have a concentrated, cool climate. It’s just that I knew, tasting Canadian wines blind whilst living in Oregon, that wines like those I have named could eventually be produced here. And great Chardonnays, too. Long before arriving, I knew we could go more for the Puligny model than the California or Aussie one. That is what I am proudest of; that even while being acclimatized to the fabulously lush and concentrated Oregon Pinots, I saw Niagara’s (and specifically the Bench’s) potential before coming. But then I’ve had an advantage, knowing Karl Kaiser and the Boscs (of Chateau des Charmes) for years. They (and others) were the first to see the potential. In short, I didn’t come home out of dumb sense of national pride. I came because the potential flavours here excited me. But I am full of national pride now, of course!

TA: When you first saw the Clos Jordanne site and its contiguous vineyards, what was your impression as to what style of wine you could make from this soil and microclimate?

TB: They were little sticks in the ground. There was no winery. I made the first vintage in 1-tonne plastic bins in the Jackson-Triggs loading dock. I walked into the LCJ vineyard alone in the late, cool wet spring of 2003, took a big breath and said: ‘Thomas, have you bitten off more than you can chew?’ But the Clos was so beautiful, so special (and Jean-Charles Boisset was whispering in my ear "This site will be great") that I just put my head down and never wavered in my ideals. We’re about to finish our fourth vineyard season and hence make our fourth vintage of wines.

Pascal Marchand never wavered either. It was great to have him at the other end of a telephone in the early days. It was hard, you know, being all alone on this, except for my wife Mary who has also pulled for LCJ from the beginning. Pascal was a big part of my ‘self-help’ group! I have known Pascal as long as I’ve known Karl. I met him the minute I went to Burgundy and this fellow Quebecois just so impressed me from the moment I met him. Both he and Bernard Zito (both ex-of Boisset’s Domaine de la Vougeraie, where Pascal

Thomas Bachelder (TB): This is a very personal subject for me, being an ex-journalist. To start with, I believe that there are interesting cool-climate varieties from Eastern Europe that have barely begun to be tapped. There are surely some great treasures awaiting us there, but as they haven’t yet discovered and marketed them successfully to a broader market themselves,

it sure isn’t up to us in Niagara to do it first!

it sure isn’t up to us in Niagara to do it first!So, working with the grape types we already know, and mindful of Niagara’s need to focus, I would favour only three cool-climate ones that have an affinity for calcaire (limestone). What I mean by that is: varieties that in the presence of limestone show thrilling floral notes, racy acidity and elegant minerality, which create the signature of a ‘sense of place’. To me, that would be: Pinot Noir; Chardonnay; and Riesling. Period. After that, perhaps Gamay (it prefers granitic soils, though) and Cabernet Franc. But Aligoté could be tested; as could Melon de Bourgogne (it is at Malivoire); Auxerrois; Pinot Blanc and Pinot Gris; Grüner Veltliner, and St. Laurent from Austria (Karl Kaiser at Inniskillin did these, but not, I believe, on the Bench). Some of these have winter hardy issues, though.

TA: In your opinion are too many varieties being grown there?

TB: Far, far too many! We need to focus, like other recent emerging regions have: Oregon, Central Otago; Washington. Niagara is both blessed and damned to have Toronto and Buffalo so close. The ready market has kept us from lifting our eyes to the world stage, which means we have remained provincial and unfocussed in our choices, or lack of them!

TA: What is it about the Escarpment that makes it different from vineyards on the plain?

TB: First, it is close enough for lake effect -- it is actually warm up here in summer! And yet, it also has slope, drainage; and that heady mix of glacial till (limestone) and silty sand that seems to imbue these wines with an outrageous perfume and a sense of place to boot! The glaciers brought limestone to the Canadian Shield in a very heterogeneous way. That is to say no two vineyards are alike. We’re finding huge differences in the soils and wines made thereon even within our single-vineyards.

TA: Why did you choose to leave Oregon to make wine in Ontario and what is the major challenge in this region?

TB: I like concentrated wines, but I love racy wines. I’m all about concentrated cool climate. I prefer wines that ally finesse, perfume and power. Power alone rarely impresses my palate. I like wines that you’re still smelling after the meal is over and the glass is empty. Wines that evolve over the course of a meal.

So, as an example, if I’m in a wine store that has every grower and village in Burgundy represented, my hands will unerringly reach out for the terroirs that best capture the duality of raciness, aroma and power. Chambolle, but of course! But also and equally, Vosne-Romanée, Volnay, even the best crus of Pernand (Ile de Vergelesses), all at least at the 1er Cru single-vineyard level.

Pinots from the minerally soils of Chassagne, Santenay and Nuits are in another category for me: perfumed and racy, but with a harder, iron-tasting core. I like those just as well, but in a more intellectual and less hedonistic way. Others, like Pommard, Corton, Savigny and Beaune strike me as being big, solid, lush Pinots that often fail to ‘make me dream.’ There are of course, exceptions.

This is not to say that Oregon doesn’t also have a concentrated, cool climate. It’s just that I knew, tasting Canadian wines blind whilst living in Oregon, that wines like those I have named could eventually be produced here. And great Chardonnays, too. Long before arriving, I knew we could go more for the Puligny model than the California or Aussie one. That is what I am proudest of; that even while being acclimatized to the fabulously lush and concentrated Oregon Pinots, I saw Niagara’s (and specifically the Bench’s) potential before coming. But then I’ve had an advantage, knowing Karl Kaiser and the Boscs (of Chateau des Charmes) for years. They (and others) were the first to see the potential. In short, I didn’t come home out of dumb sense of national pride. I came because the potential flavours here excited me. But I am full of national pride now, of course!

TA: When you first saw the Clos Jordanne site and its contiguous vineyards, what was your impression as to what style of wine you could make from this soil and microclimate?

TB: They were little sticks in the ground. There was no winery. I made the first vintage in 1-tonne plastic bins in the Jackson-Triggs loading dock. I walked into the LCJ vineyard alone in the late, cool wet spring of 2003, took a big breath and said: ‘Thomas, have you bitten off more than you can chew?’ But the Clos was so beautiful, so special (and Jean-Charles Boisset was whispering in my ear "This site will be great") that I just put my head down and never wavered in my ideals. We’re about to finish our fourth vineyard season and hence make our fourth vintage of wines.

Pascal Marchand never wavered either. It was great to have him at the other end of a telephone in the early days. It was hard, you know, being all alone on this, except for my wife Mary who has also pulled for LCJ from the beginning. Pascal was a big part of my ‘self-help’ group! I have known Pascal as long as I’ve known Karl. I met him the minute I went to Burgundy and this fellow Quebecois just so impressed me from the moment I met him. Both he and Bernard Zito (both ex-of Boisset’s Domaine de la Vougeraie, where Pascal