Amador County is part of the vast Sierra Foothills AVA, which spans from just beyond the Central Valley to the Sierra Nevada Range, taking in with it a wide range of terrain and growing conditions.

Amador County is part of the vast Sierra Foothills AVA, which spans from just beyond the Central Valley to the Sierra Nevada Range, taking in with it a wide range of terrain and growing conditions.

Is Amador California’s Last Great

Undiscovered Wine Region?

Our premier Best-of-Appellation tasting inspires a brief history and tour of just one area in the vast Sierra Foothills AVA, along with some tasty wine notes about some Gold and Silver medalists.

by Stan Hock

May 16, 2008

t’s ironic that what some consider California’s last great undiscovered wine region has a winemaking history dating back 150 years. Long before a handful of wine writers convinced Americans that they should be drinking super-extracted red wines, Amador County in the Sierra Foothills had a corner on the style; yet today it escapes the glare of vinous approbation received by once-overlooked regions, such as Paso Robles.

t’s ironic that what some consider California’s last great undiscovered wine region has a winemaking history dating back 150 years. Long before a handful of wine writers convinced Americans that they should be drinking super-extracted red wines, Amador County in the Sierra Foothills had a corner on the style; yet today it escapes the glare of vinous approbation received by once-overlooked regions, such as Paso Robles.

Amador is in the heart of California's scenic Gold Country, an historic wine region that also encompasses El Dorado, Calaveras and Nevada counties. It was here, in the rugged western foothills of the majestic Sierra Nevada mountain range that the state’s wine industry took flight during the Gold Rush. As fortune seekers, many of them European, flocked to the Sierras to prospect for gold, small wineries arose to help slake their thirst. Within a few decades, there were more wineries in the “Mother Lode” than in any other region of California. Some vines planted during that era survive to this day.

The decline of gold mining at the end of the 19th-century, followed by Prohibition in 1920, laid low this frontier wine community, which remained dormant until the late 1960s. At that time, a new generation of pioneers began migrating to the Gold Country, drawn by the region's rolling, sun-drenched hillsides, warm climate, and volcanic, decomposed granite soils – ideal conditions for cultivating high-quality wine grapes. When their robustly flavored red wines began attracting the attention of wine lovers, the historic Sierra Foothills wine region was reborn.

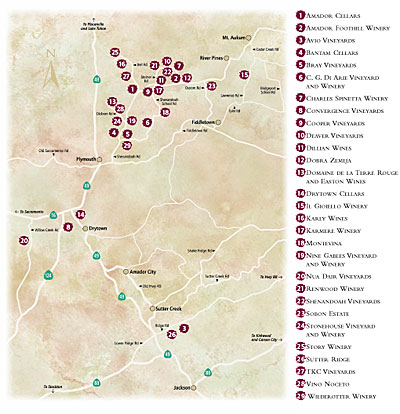

Today, Amador boasts 40 wineries and 3,000 acres of wine grapes, a high percentage of which are farmed organically. The majority are in the northern part of the county in the Shenandoah Valley and Fiddletown appellations, near the small town of Plymouth.

Growing Conditions

In these areas, vines are planted almost exclusively on rolling, oak-studded hillsides – ranging from 1,200 to over 2,000 feet in elevation – in Sierra Series

Amador County AVA spans a large region, just a fraction of the Sierra Foothill appellations.

Map courtesy of Amador Vintners

Amador has a warm climate (classified as a high Region 111 in the UC Davis heat summation system) comparable to northern Napa Valley. Although it heats up early in the day, temperatures rarely exceed 100 degrees, a common occurrence in other California wine regions. Equally important, temperatures typically drop 30-35 degrees in the evening as breezes cascade down from the Sierras. This rapid cooling helps Amador grapes retain the acidity essential to balanced wines.

Amador's production of robust, intensely flavored red wines also reflects its high percentage of old vines: roughly 600 acres are 60 years or older, including several vineyards dating to the 19th century. These deeply rooted, head-trained vines are responsible for the intense, concentrated Zinfandels for which Amador County is renowned.

Diversity and change

Until recently, Zinfandel was the predominant grape in the foothills but now Rhone varietals are rapidly increasing in acreage.

Given its history and scenic environment, one wonders why these wines have yet to be fully discovered, especially by fans of blockbuster reds. True, Amador is a bit off the beaten path (45 miles east of Sacramento and a two-hour drive from the San Francisco Bay Area) and doesn’t offer ‘mainstream’ varieties (Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, etc.), but it’s a beautifully rustic area far from the madding crowd with innumerable wine nuggets of great value. By and large, Amador wines are half the cost of comparable wines from coastal regions.

One needs to revisit the 1970s and ‘80s to understand why Amador has a lingering identity problem. After rugged Zinfandels from Sutter Home, Montevina, Ridge, Carneros Creek and Mayacamas wineries put Amador on the fine wine map in the early 1970s, a new generation of wine pioneers migrated to the region. But, unlike the doctors, lawyers and Indian chiefs who flocked to Napa Valley, these folks – mostly home winemakers from the San Francisco Bay Area – lacked the means to hire trained winemakers or purchase new equipment.

Many were weekend wine warriors whose ambition was to sell a few hundred cases annually to visitors to their makeshift tasting rooms. Not surprisingly, wine quality varied considerably, with high volatile acidity, astringent tannins and funky cooperage sometimes marring the region’s intense, spicy fruit. In an era predating the “bigger is better” ethos, many consumers, retailers and wine writers simply didn’t appreciate what Amador had to offer. (On the other hand, many red wine lovers became and remain rabid Amador fans.)

During the 1990s, a group of Amador wineries emerged with the capital, technical expertise and determination to produce quality wines on a consistent basis and market them nationally. These included Montevina, Shenandoah Vineyards (and its sister winery, Sobon Estate), Karly, Amador Foothill, Domaine de la Terre Rouge (a Syrah specialist), Vino Noceto (which introduced Sangiovese to the region) and Renwood (which made a splash with a half-dozen rich, polished Zinfandels.) The rest of the region’s wineries, however, remained fairly provincial.

Since 2000, the quality ethos of the vanguard group has spread throughout the region as grape growers apply modern vineyard management techniques, wineries acquire new, quality crushers and presses, and winemakers more thoroughly master their art. Key to this evolution has been an infusion of fresh blood, as a dozen new wineries have emerged on the scene, many led by savvy young entrepreneurs committed to making fine wine and expanding their reach beyond the region’s traditional – and aging – Sacramento-area customer base. Amador’s tasting rooms are now filled with far-flung Millennial-generation consumers avidly searching the hills for liquid gold.

The APPELLATION AMERICA tasting panel: (from left) Alan Goldfarb, Cour

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

click here

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

click here

Print this article | Email this article | More about Amador County | More from Stan Hock