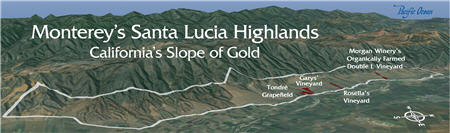

Click Here for an interactive map that provides an enlightening perspective of the Santa Lucia Highlands.

Click Here for an interactive map that provides an enlightening perspective of the Santa Lucia Highlands.

Santa Lucia Highlands Vintners Carve Out Artisan Niche In Monterey

The place for Pinot...and Chardonnay

by Laurie Daniel

September 17, 2008

hile much of Monterey County is known for its large-scale grape farming and good-value wines, the Santa Lucia Highlands appellation has managed to set itself apart as a home of artisan viticulture and winemaking.

hile much of Monterey County is known for its large-scale grape farming and good-value wines, the Santa Lucia Highlands appellation has managed to set itself apart as a home of artisan viticulture and winemaking.

The 18-mile-long appellation - situated on benchland above the western edge of the Salinas Valley - has a climate similar to that found in nearby parts of the valley, so that doesn’t account for the quality difference. Both areas are influenced by the wind and fog off Monterey Bay and have good conditions for cool-climate grapes like Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. There are significant differences in the soils - those in the Highlands are shallower and less fertile than those on the valley floor - and the appellation is in the shadow of the Santa Lucia Mountains and protected from harsh afternoon sun.

But perhaps the most important difference is mindset. In the Santa Lucia Highlands, says Rich Smith, whose family owns Paraiso Vineyards, “there’s more artisan farming and less commercial farming because there’s more artisan winemaking and interest in small lots.”

Dan Lee, owner of Morgan Winery, gets the word out about the magic of the Santa Lucia Highlands.

There’s some mechanization in the appellation, especially in the larger vineyards, but a lot of the vineyard work is done by hand, especially in the smaller parcels. The focus on quality has prompted big demand for the grapes. High-end wineries from outside the appellation, like Siduri, Testarossa, Arcadian, Loring, Tantara and Patz & Hall, are among the producers that make wines from the Santa Lucia Highlands, an AVA since 1992.

To illustrate the demand for grapes, Steve McIntyre, who farms three parcels totaling about 300 acres in the Highlands (and an additional 7,000 acres elsewhere in Monterey with his company, Monterey Pacific), relates the average prices paid for Pinot Noir. In the Santa Lucia Highlands, he says, Pinot goes for about $4,000 a ton, vs. $2,800 in nearby Arroyo Seco and $1,900 in the broader Monterey AVA. He adds that a lot of grape contracts in the Highlands are by the acre, rather than by the ton, so the buyer can have the grapes farmed to his or her specifications. That’s rare elsewhere in Monterey, McIntyre says.

As a result, you won’t find $10 Chardonnay or $15 Pinot from the Santa Lucia Highlands. Most of the wines are in the $30-and-up category.

Some of the most prized and coveted Pinot Noir and Chardonnay comes from the vineyards on the Santa Lucia Highlands bench outlined here.

“That’s going to be the signature grape for the Highlands from here on out,” Lee says.

Our BEST-OF-APPELLATION tasting found a number of outstanding Pinots from the Santa Lucia Highlands, wines that displayed great depth and intensity, along with cherry/berry flavors and notes of rose petals and earth. The long, cool growing season “allows us to capture all those flavors,” says Gary Franscioni, who owns Rosella’s Vineyard and co-owns Garys’ Vineyard with Gary Pisoni, who also owns the famed Pisoni Vineyard. (Rosella’s, Garys’ and Pisoni were fruit sources for a number of the BOA Pinots, including bottlings from Siduri, Pelerin and Tantara.)

Still, early efforts with Pinot in the appellation – the first Pinot was planted in 1973 - met with mixed results. Until the mid-‘90s, Smith says, the only Pinot planted in the Santa Lucia Highlands was the Martini clone. His Pinots at Paraiso Vineyards were so pale that he planted a little Syrah with an eye to beefing up the Pinot. McIntyre says that the Pinot Noir planted in the vineyard his family bought in

![hahn_estates [ copyright steve-gunnerson]](http://wine.appellationamerica.com/images/appellations/features/hahn_estates[steve-gunnerson]330.jpg)

The view from Hahn Estates shows the Santa Lucia Highlands in relation to the Salinas Valley floor beyond.

Smith, for his part, credits Franscioni and Pisoni for lifting everyone’s game when it comes to Pinot Noir. The “two Garys” were from longtime Monterey produce-growing families and developed an interest in wine. Pisoni started planting Pisoni Vineyard in 1982; Franscioni planted Rosella’s (named for his wife) in 1996; and the two teamed up on Garys’ in 1997. Then, Smith says, “they went out and picked people that they wanted to work with,” mostly winemakers from outside the area.

When their wines were well-received, consumers and critics started asking where these great wines were from. “The wine was famous before the region was,” Smith says.

Don’t Overlook SLH Chardonnay

With all the accolades that the Pinots have received, it’s easy to overlook the Chardonnay. Santa Lucia Highlands Chardonnay ranges from lean and lemony to rich and tropical, but all the wines have a firm core of acidity. Acid levels in the grapes tend to be so high, in fact, that harvest becomes a waiting game as vintners wait for the acids to drop. “We have the ability to go through some malolactic fermentation in the wines without losing the acidity,” Lee says. “You can bend it in a style you like.”That Ain’t No Termato...That’s My Wine

Monterey Hones Its Identity

The Appellation Defining Wines of the Monterey Region

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

click here

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

click here

Print this article | Email this article | More about Santa Lucia Highlands | More from Laurie Daniel