Mount Harlan’s Natural Miracle

by Clark Smith

May 12, 2009

The average appellation has dozens of wineries making hundreds of wines. With a single winery, Calera Wine Company, and three varietals, Mount Harlan is part of a small club of micro-AVAs, most of which are confined by land area. But Mount Harlan encompasses over 7,000 acres, of which a scant 100 were planted by one man with a hellish commute. What is he doing in this punishing high desert no one else will live in? You guessed it – even by wine industry standards, Josh Jenson is nuts.

ES, Josh Jenson is nuts about limestone. That single word distinguishes this tiny region from everything else in California. Mount Harlan provides California with just about our only window on the French claim about the importance of this bedrock to their great Burgundies. There are, to be sure, other calcareous areas, notably the shales of Paso Robles west side, but true limestone is not a California thing, unless you count the Mohave Desert and Death Valley, which is not exactly Pinot Country.

ES, Josh Jenson is nuts about limestone. That single word distinguishes this tiny region from everything else in California. Mount Harlan provides California with just about our only window on the French claim about the importance of this bedrock to their great Burgundies. There are, to be sure, other calcareous areas, notably the shales of Paso Robles west side, but true limestone is not a California thing, unless you count the Mohave Desert and Death Valley, which is not exactly Pinot Country.

Still, natural features such as limestone deposits do not tell the whole story, unless you want to count Josh Jenson as a force of nature. It’s easy to believe that his

The Selleck Vineyard reveals a cap of limestone which is omnipresent throughout Mt. Harlan.

The Burgundians are nuts about limestone, too. After two crushes in the Côte D’Or in ‘70 and ‘71, Josh had swallowed whole their theory that calcaire, not weather, is their source of greatness. “Two hundred yards from the greatest vineyards in the world, they don’t even plant grapes anymore – it’s all potatoes and such, because they know Pinot from that soil will be very ordinary.”

Climate-oriented viticulturalists scoff. Yeah, right. But for three decades, the wines of Calera have spoken volumes in defense of Jensen’s harebrained notion. More than any other California Pinots, they closely mimic the Côte d’Or, despite the obvious - this high altitude desert has little in common with Burgundy’s climate.

“Limestone interacts with the vine’s roots and somehow makes grapes more complex,” Jensen offers. “You don’t just get one-dimensional varietal fruit; you get secondary and tertiary aromas and flavors.”

Leading terroir guru Claude Bourguignon extolls the vine’s unique relationship to chalk, which is not really a soil at all, but compacted oyster shells - almost pure calcium carbonate but also rich in trace minerals, packed and compressed over millions of years into a solid block, with a life-killing pH of 11.

According to his view, vines are among the few plants whose roots can penetrate, neutralizing the chalk and creating a zone where fungi, bacteria, and worms can join the party. This trace mineral uptake, facilitated by mycorrhizal fungi, gives wines their intense mineral finish, and conveys flavor dimensionality, as well as anti-oxidative power and longevity.

Part of the complexity apparent in Calera’s offerings undoubtedly stems from the natural winemaking practices Jensen learned by studying Domaine Dujac and Domaine Romani Conti, traditional methods evolved to handle limestone-derived wines. Since he emphasizes gentle handling, Josh bought an old cliffside rock crushing plant already set up for seven levels of gravity feed – minimizing pumping. Native yeast, whole clusters, 100% stems, ageing on fine yeast lees, rarely racking, and the avoidance of filtration figure in. Yet sample his Central Coast blend, made exactly as the others. While it shares their funky rusticity, its comparative shallowness stands as clear evidence that Mt. Harlan’s special terroir matters.

Like five brothers, the vineyard-appellated Mount Harlan AVA blood siblings show great differences in size and affability, but all carry familial traits which extend as well to their sisters, the Mount Harlan whites - complexity, longevity, and classically proportioned structure. Indeed, their resemblance to the Côte d’Or sums it up, and clearly Josh’s crazy gamble has paid off in spades. Like their French antecedents, these wines combine focused, driving energy with balance, subtlety and elegant restraint. The Central Coast misnamed “Mt. Harlan Cuvee” is definitely an adopted child, raised in the same home. Through its differences from the blood family, it provides a look at “nature vs nurture” - the contribution of winemaking as opposed to terroir.

Like five brothers, the vineyard-appellated Mount Harlan AVA blood siblings show great differences in size and affability, but all carry familial traits which extend as well to their sisters, the Mount Harlan whites - complexity, longevity, and classically proportioned structure. Indeed, their resemblance to the Côte d’Or sums it up, and clearly Josh’s crazy gamble has paid off in spades. Like their French antecedents, these wines combine focused, driving energy with balance, subtlety and elegant restraint. The Central Coast misnamed “Mt. Harlan Cuvee” is definitely an adopted child, raised in the same home. Through its differences from the blood family, it provides a look at “nature vs nurture” - the contribution of winemaking as opposed to terroir.

Selleck Vineyard Like Reed and Jensen, these 4.8 acres were planted in 1975 - same rootstock, same Côte d’Or clone, the only variable being variations in soil, and aspect, in this case a rocky southwest-facing slope. With its great sun exposure, this vineyard produces Calera’s most concentrated fruit and lowest yield, generally a scant ton per acre.

Probably the best of the '05 Calera's, the 2005 Selleck is also the least generous at this stage due to its solid tannins and extreme minerality. Closed as it is, there is much in the nose - soulful aged Parmesan, orange peel, bow rosin, lemon oil, sage, bay leaf, and mace. The mouth has sufficient depth and complexity to challenge the great Côte d'Or, with driving energy which begs for cellaring.

Hangtime is clearly not the key to increased structure here. Selleck is picked in mid-September, usually the first vineyard harvested, and makes the most expensive wine, with full flavored, masculine tannin which commands top prices.

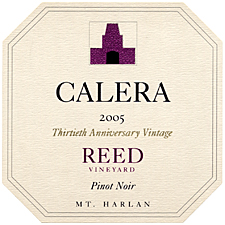

Reed Vineyard The only difference with Selleck is its rockier soil, which seems to decrease its yield, and the Reed’s North-facing

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

click here

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

click here

Print this article | Email this article | More about Mount Harlan | More from Clark Smith